|

DOI: 10.7256/2453-8922.2022.3.38555

EDN: JHLNJJ

Received:

02-08-2022

Published:

31-10-2022

Abstract:

The purpose of this work was to determine the range of changes in the Fourier criterion (number) when predicting the thermal regime of dispersed rocks in thawed and frozen state. And, also an assessment of the possibility of averaging the thermophysical characteristics of rocks to obtain universal values of Fourier numbers. To achieve this goal, an assessment of the influence of the thermophysical properties of dispersed rocks on the range of changes in the values of the Fourier number used in thermal calculations of technical objects of the cryolithozone is made. The calculation formulas took into account the functional dependence of the coefficient of thermal conductivity, density and specific heat capacity of rocks on humidity (iciness) in the thawed and frozen state. As an example, a mixture of quartz sandstone with water in a thawed and frozen state is considered when the ice content changes from zero (dry quartz sandstone) to full moisture saturation. It is established that the range and nature of the change in Fourier numbers for thawed and frozen dispersed rocks, depending on their humidity (iciness), differs significantly, not only quantitatively, but also qualitatively: for thawed dispersed rocks, the Fourier number decreases with increasing humidity, and for frozen rocks increases. The possibility of averaging the thermophysical characteristics of rocks to obtain universal values of Fourier numbers has been evaluated. It is shown that the use of universal Fourier numbers leads to a significant error for both thawed and frozen rocks and their use in thermal calculations with annual temperature fluctuations is impractical.

Keywords:

criteria, forecast, thermal mode, thawing, dispersed rock, cryolithozone, iciness, thermal conductivity, averaging, calculation error

This article is automatically translated.

You can find original text of the article here.

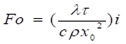

Introduction. Reliability and safety of operation of various types of engineering structures, both underground and above-ground, located in the cryolithozone, largely depend on thermal interaction with the surrounding soil or rocks. An important task of engineering geocryology is the prediction of the thermal regime of rocks and its management during the construction and operation of engineering structures in the cryolithozone. This area of research is relevant both in Russia [1, 2, 3] and in other countries [4, 5, 6], attracting wide attention of the scientific and professional engineering community. The issue becomes particularly relevant in the interaction of structures with so-called dispersed rocks, the structural strength of which changes significantly with changes in temperature and phase transitions of moisture [7, 8, 9]. For example, in [10, 11, 12] it is proved that the stability of mine workings, mines and underground tunnels of the cryolithozone is directly determined by the thermal regime of the host rocks. The interaction of main gas and oil pipelines with frozen soils [13] emphasize the need to take into account the thermal factor when choosing technical and technological means to ensure their trouble-free operation. That is, forecasting and monitoring the degree of thermal interaction of engineering structures with dispersed rocks is an urgent task, the solutions of which are in great demand in engineering practice. For example, in the works [14, 15, 16] it was established that the thermal regime of ground bases is the determining factor of safe and reliable operation of cryolithozone highways. When predicting the thermal regime of various cryolithozone engineering structures interacting with dispersed rocks, two options for presenting the initial data and the results of the solution are possible: an explicit view with dimensional units of measurement and a criterion (dimensionless) view. The second approach is more convenient, since it allows you to simplify the solution of thermophysical problems by reducing the number of variables. In addition, it allows for a more generalized analysis of the results, covering a wide range of possible changes in the characteristic data that determine thermal processes both in the object under study and in the surrounding rocks. One of the main criteria is the Fourier number, which determines the intensity and speed of thermal processes. A feature of thermophysical calculations of dispersed rocks using the Fourier number is its dependence on the aggregate state of moisture in rocks, since the thermophysical characteristics of thawed and frozen rocks differ significantly [1, 3]. Using different values of the Fourier number is not very convenient, since usually annual changes in the temperature of the active soil layer in a particular structure are taken into account in thermal calculations. In this case, it is advisable, but not always possible, to use universal Fourier numbers. Universal Fourier numbers are based on the averaged thermal characteristics of rocks in thawed and frozen state. At the same time, it is necessary to estimate the errors that may arise when determining Fourier numbers for thawed and frozen rocks when replacing them with universal values. The purpose of this work was to determine the range of changes in the Fourier criterion for predicting the thermal regime of dispersed rocks in thawed and frozen state. And, also, an assessment of the possibility of averaging the thermophysical characteristics of rocks to obtain universal values of Fourier numbers for thermal calculations. Calculation methodThe complex dimensionless variable, which is called the Fourier number (criterion), is determined by the formula [17]: |

| (1) | Here : ? is the coefficient of thermal conductivity of rocks, W/mK; p is the density of rocks, kg/m3; s is the specific heat capacity of rocks, kJ/kgK; ? is time, s. x0 is a constant metric value (can be assumed to be equal to 1.0 m), m. Since we consider rocks in two states – thawed and frozen, their thermophysical properties will be different. Therefore, the parameter "i" was introduced, which in the future will mean "1" for thawed rocks and "2" for frozen rocks. If heat exchange processes occur in rocks without phase transformations of moisture, then the Fourier number changes only in time. In this case, it is also sometimes called "dimensionless" or "relative" time. But, according to the author, this is not entirely correct. The following formulation is more acceptable [18]: the Fourier number is the ratio between the rate of change of thermal conditions in the environment and the rate of adjustment of the temperature field inside the system (body) under consideration, which depends on the size of the body and its thermal conductivity coefficient. For clarity , let 's check the dimension of the number Fo . The dimension of the numerator is equal to: [(W/m·K)*(s)] = [J/m·K]. The dimension of the denominator is: [(m2)*(J/kg·K)*(kg/m3] = [J/m·K]. The dimension of the denominator is identical to the dimension of the numerator, i.e. the Fourier number itself has no dimension. Since the physical properties of dispersed rocks are largely determined by the degree of their humidity (iciness), in general, the formula (1) should include the functional dependencies p(W) and C(W). For example, consider sand rocks. For a mixture of quartz sand and ice, the specific heat capacity of rocks and the bulk mass can be determined by the following formulas. The dependence of the specific heat capacity of the rock in the thawed (i=1) and frozen (i=2) state can be written as:

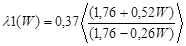

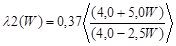

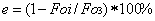

| C1 = 0.835·(1-W) +4.2W ; C2 = 0.835· (1-W) +2.1W. | (2) | | | | Here: 0.835 – specific heat capacity of dry sand, kJ /kg * K; 2.1 – specific heat capacity of ice, kJ/kg* K; 4.2 – specific heat capacity of water, kJ/kg *K. The dependence of the bulk mass (density) on humidity (i=1) and iciness (i=2) of sand can be written as: | ?1 = 2500(1-W) + 1000W=2500 -1500W; ?2 = 2500(1-W) + 900W =2500 -1600W. | (3) | | | | Here: 2500 – volume mass of quartz sand, kg/m3; 900 – volume mass of ice, kg/m3; 1000 – volume mass of water, kg/m3. The thermal conductivity coefficient of the binary mixture can be calculated according to the formula of V.I.Odelevsky [19,20]. Taking into account that the thermal conductivity coefficient of water is 0.56 W/mK; the thermal conductivity coefficient of ice is 2.24 W/mK; the thermal conductivity coefficient of dry sand is assumed to be 0.37 W/mK; the thermal conductivity coefficient of ice is 2.24 W/mK; the coefficient of the thermal conductivity of water is 0.56 W / mK. For thawed and frozen rocks, the coefficient of thermal conductivity depending on humidity (iciness) was determined by the formulas obtained in [17] |   | (4) | | | | The relative error in determining the Fourier number when averaging the characteristics of a dispersed rock can be determined by the formula |

| (5) | Here Fo 3 is the Fourier number obtained with the averaged properties of the dispersed rock. And here it is necessary to evaluate not only the dependence of the relative error on the humidity (iciness) of the dispersed rock, but also the maximum error that will occur. That is, the Fourier numbers in summer and winter should be calculated at the maximum possible humidity (iciness) of dispersed rocks. Results and discussion.

The graphs (Fig. 1) show calculations using formulas (4). Which also shows the values of the deviation of the values of the thermal conductivity coefficient of the rock in the thawed ?1(W) and frozen ?2(W) state between themselves and the average value of the thermal conductivity coefficient ?3(W), determined by the formulas: ?3(W) = (?2(W) + ?1(W))/2 – curve 3; E1 =?3(W) – ?1(W) – curve 4; E2 =?3(W) – ?2(W) – curve 5.

Fig. 1. Change in the thermal conductivity coefficient of dispersed rock in the thawed and frozen state: 1 – in the thawed; 2 – in the frozen; 3 – average value; 4 – deviation of the average value from the value in the thawed state; 5 - deviation of the average value from the value in the frozen state. With sufficient accuracy for engineering calculations, the expression for the average value of the thermal conductivity coefficient can be calculated by the formula: ?3(W) = 0.37 + 0.51W. The interval of change of the Fourier numbers for the winter and summer periods depending on the iciness (humidity) can be determined by the formula (1) using the calculated data of the table. Change in the properties of dispersed rock from humidity (iciness) TableW, % | | ?1 W/m·K | ?2 W/m·K | ?3 W/m·K | c1 J/kgK | c2 J/kgK | c3 J/kgK | ?1 kg/m3

| ?2 kg/m3?3 | kg/m30 | | | 0,37 | 0,37 | 0,37 | 835,0 | 835,0 | 835,0 | 2500 | 2500 | 2500 | | 10 |

0,38 | 0,44 | 0,41 | 1171,5 | 961,5 | 1066,5 | 2600 | 2590 | 2595 | | 20 | 0,40 | 0,53 | 0,47 | 1508,0 |

1060,3 | 1284,2 | 2700 | 2680 | 2690 | | 30 | 0,42 | 0,63 | 0,53 | 1844,5 | 1214,5 | 1529,5 | 2800 | 2770 |

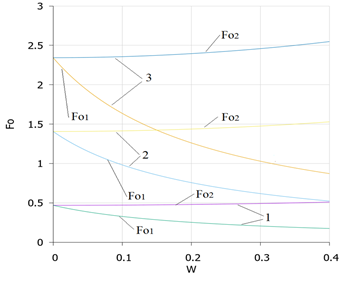

2785 | | 40 | 0,44 | 0,74 | 0,59 | 2181,0 | 1341,0 | 1761,0 | 2900 | 2860 | 2880 | At the same time, such an important indicator affecting the absolute value of the Fourier number as time, expressed in seconds, can be found by the simple formula ? = N * 2,635* 106, s. Here N is the number of months in the period under consideration. Fig. 2 shows the results of calculating Fourier numbers for frozen and thawed dispersed rocks depending on their iciness (humidity) in different time periods.

Fig.2. Change in the Fourier number (Fo1 – thawed rocks; Fo2 – frozen rocks) depending on the humidity (iciness) of the dispersed rock (ie) with different duration of the thermal process: 1 - one month: 2 - two months; 3 - five months.

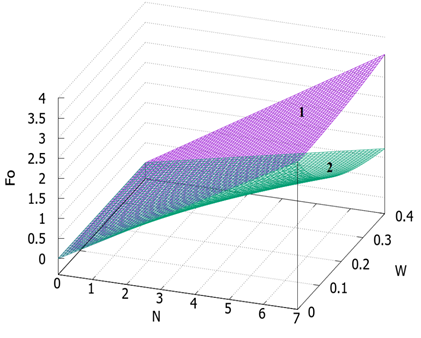

The analysis of the graphs in the figure allows us to draw an important conclusion: for thawed dispersed rocks, the Fourier number decreases with increasing humidity, and for frozen rocks it increases. At the same time, the rates of decline and increase are different. Thus, with an increase in rock moisture from 10 to 40% (a four-fold change), the Fourier number for frozen rocks increases by only 1.1 times. A, the degree of decrease in the Fourier number for thawed rocks in the same range is 1.8, which is almost 1.6 times greater than the degree of increase in the Fourier number for frozen rocks. For clarity of the conclusion made, Figure 3 shows a 3D graph of the range of changes in the Fourier number for thawed and frozen rocks depending on their moisture content of ice in a wide time interval.

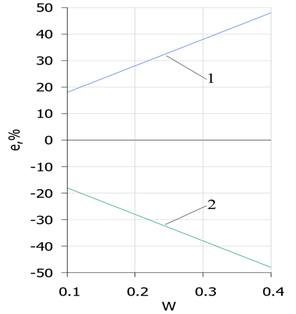

Fig. 3. The change in the Fourier number depending on the humidity (iciness) of the dispersed rock for different duration of the thermal process (N – months): 1 – frozen rocks; 2 – thawed rocks. Thus, it becomes obvious that the Fourier numbers for thermal processes occurring in frozen and thawed rocks differ not only quantitatively, but also qualitatively, which must be taken into account when solving specific tasks for forecasting and evaluating the formation of the thermal regime of various objects in the cryolithozone. The graph Fig.4 shows the results of calculations to determine the error of averaging the Fourier numbers for the summer and winter period of the year, depending on the humidity (iciness) of the dispersed rock. Which in the range of humidity (ice content) of the rock from 10 to 40% can be described by a simple linear function of the form e = abs (0.08+w)*100, %.

Fig. 4. Error in determining the Fourier number when averaging the values of thermophysical properties depending on the humidity (iciness) of the dispersed rock: 1 – thawed rocks; 2 – frozen rocks. As can be seen from the graphs in the figure, in the characteristic range of humidity (iciness) of dispersed rocks of 10-40%, errors are significant for both thawed and frozen rocks. Moreover, with an increase in humidity (iciness) the error increases significantly and reaches 48% at the maximum moisture content (when the entire pore space is filled with moisture). And, at 10% humidity is 18%, which is almost 2 times higher than the maximum permissible error allowed in engineering calculations. The qualitative and quantitative analysis has shown that it is impractical to use universal Fourier numbers in thermal calculations of dispersed rocks, since the errors that arise in this case are significant and cannot be ignored. All thermal calculations should be divided into three components: calculation in the thawed state; calculation in the frozen state; calculation during the transition period of freezing-thawing of rocks. Conclusion. As a result of the conducted research, it was found that the Fourier numbers for thermal processes occurring in frozen and thawed dispersed rocks differ not only quantitatively, but also qualitatively. This should be taken into account when solving specific tasks for the prediction and assessment of the formation of the thermal regime of dispersed rocks of the cryolithozone. For thawed dispersed rocks, the Fourier number decreases with increasing humidity, and for frozen rocks it increases with increasing iciness. At the same time, the rates of decline and increase are different. Thus, with an increase in rock moisture from 10 to 40% (a four-fold change), the Fourier number for frozen rocks increases by only 1.1 times. A, the degree of decrease in the Fourier number for thawed rocks in the same range is 1.8 times, which is almost 1.6 times greater than the degree of increase in the Fourier number for frozen rocks. The use of universal Fourier numbers in the characteristic range of humidity (iciness) of dispersed rocks of 10-40% leads to a significant error, both for thawed and frozen rocks. Moreover, with an increase in humidity (iciness) the error increases significantly and reaches 48% at the maximum moisture content (when the entire pore space is filled with moisture). And, at 10% humidity is 18%, which is almost 2 times higher than the maximum permissible error allowed in engineering calculations. The use of universal Fourier numbers in thermal calculations with annual temperature fluctuations is impractical. It is correct to divide thermal calculations into three components: calculation of rocks in a thawed state; calculation of rocks in a frozen state; calculation during the transition period of freezing-thawing of rocks. With the corresponding calculation of Fourier numbers for each period and the aggregate state of moisture in dispersed rocks. The article will be useful as engineers involved in the design of technical facilities in the cryolithozone, and scientists in the field of construction physics and geocryology. In methodological terms, the article will be of interest to teachers and graduate students studying in various specialties of the direction 1.6. "Earth Sciences" (specialty 1.6.7. "Engineering geology, permafrost and soil science"). and 2.1 "Technical sciences", in particular – the educational specialty 08.02.05 "Construction and operation of highways and airfields". It is advisable to direct further research to study the influence of the thermophysical properties of dispersed rocks on the range of changes in the main criteria of heat exchange, in particular on the interval of change in the Bio and Stefan numbers, taking into account their variability for thawed and frozen rocks.

References

1. Kuzmin G.P. Underground structures in cryolithozone. Novosibirsk: Nauka, 2002.-176 p.

2. Galkin A.F., Pankov V.Yu. Influence of iceness of the soil on the depth of thawing of the road base // Arktika i Antarctica. 2022. ¹ 2. S.13-19.

3. Zheleznyak I. I., Sakisyan R. M. Methods of management of seasonal freezing of soils in Transbaikalia. Novosibirsk: Nauka. 1987.-128 p.

4. Eppelbaum, L.V., Kutasov, I.M. Well drilling in permafrost regions: Dynamics of the thawed zone.Polar Research, 2019, 38, 3351

5. M. Li, H. Chaouki, J.L. Robert, D. Ziegler, D. Martin, M. Fafard. Numerical simulation of Stefan problem with ensuing melt flow through XFEM/level set method// Finite Elements in Analysis and Design, Vol. 148, 2018, pp. 13-26.

6. John Crepeau, Ali S. Siahpush. Solid–liquid phase change driven by internal heat generation//Comptes Rendus Mécanique. Vol. 340, Issue 7, 2012, pp. 471-476.

7. Xu G., Qi J., Wu W. (2019) Temperature Effect on the Compressive Strength of Frozen Soils: A Review. In: Wu W. (eds) Recent Advances in Geotechnical Research. Springer Series in Geomechanics and Geoengineering. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-89671-7_19

8. Andersland O., Ladanyi, B .: Frozen Ground Engineering. Wiley, URL https://books.google.at/books?id=UyUZ_7o48U0C (2004)

9. Hu, X.D., Wang, J.T., Yu, X.F.: Laboratory test of uniaxial compressive strength of shanghai frozen soils under freeze-thaw cycle. Mater. Sci. Technol. II, Trans. Tech. Publications, Adv. Mater. Res. 716, 688–692 (2013). https://doi.org/10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMR.716.688

10. Dyadkin Yu.D. Fundamentals of Mining Thermophysics for Mines and Mines of the North. M.: Nedra, 1968.-256s.

11. Scuba V.N. Study of the stability of mine workings in permafrost conditions. Novosibirsk: Nauka, 1974.-118 p.

12. Sherstov V.A. Increasing the stability of the workings of placer mines of the North. Novosibirsk : Nauka. Sib. otd-nie, 1980.-56 p.

13. Zhang X., Feng S.G., Chen P.C. (2013)Thawing settlement risk of running pipeline in permafrost regions. Oil Gas Storage Transporation, no.6, 365–369

14. Kondratyev V.G., Kondratyev S.V. How to protect the federal highway "Amur" Chita-Khabarovsk from dangerous engineering and geocryological processes and phenomena // Engineering geology. 2013. ¹ 5. S. 40-47.

15. Shats M.M. Sovremennoe gosudarstvennyi gorodskogo insatitel'nogo instavleniya g. Yakutska i put'nogo ravlenie ee zadozhestvennogo // Georisk. 2011. ¹2. pp. 40–46.

16. Dore, G., Cote J., Segui, P. and N. Ghafari (2019) Insulating Performance of Foam Glass Aggregate (FGA) in Cold Regions Roads and Highways. GRINCH 2019 “Groupe de Recherche en Ingénierie des Chaussées”, Waterloo, Ontario, Canada. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.19498.77768

17. Galkin A.F. Range of Change in Fourier numbers in Thermal Calculations of Automobile Roads in the Cryolithic Zone (2022). Transportation Research Procedia.V.63,pp.575-583. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trpro.2022.06.050

18. Fourier number or criterion. [Elektronnyi resurs]. – Access mode: https://dic.academic.ru/dic.nsf/ruwik%20%20%20%20%20%20i/51885 (access date: 2022.06.21).

19. Odelevsky V.I. Calculation of generalized conductivity of heterogeneous systems // ZHTF. 1951. Vol.21, vol.6. S.667-685.

20. Dulnev G.N., Zarichnyak Yu.P. Thermal conductivity of mixtures and composite materials. L.: Energiya, 1974.-264 p.

Peer Review

Peer reviewers' evaluations remain confidential and are not disclosed to the public. Only external reviews, authorized for publication by the article's author(s), are made public. Typically, these final reviews are conducted after the manuscript's revision. Adhering to our double-blind review policy, the reviewer's identity is kept confidential.

The list of publisher reviewers can be found here.

The subject of the authors' research is the technology of calculating the Fourier criterion for predicting the thermal regime of rocks in various states. The relevance of the study lies in ensuring the reliability and safety of operation of various types of engineering structures operating in the cryolithozone, which depends on the interaction of surrounding rocks and heat generation processes. The most important task of the practical direction of engineering geocryology is the prediction of the thermal regime of rocks for the management process during the construction and subsequent operation of engineering structures in the cryolithozone in the Arctic. The scientific novelty consists in the author's interpretation of the Fourier number for calculating thawed and permafrost rocks, which considers the relationship between the rate of change in thermal conditions in the environment and the rate of restructuring of the temperature field inside the system under consideration, which depends on the size of the body and its coefficient of thermal conductivity. The author's contribution consists in identifying the conditions for using the division of thermal calculations into three components: calculation of rocks in a thawed state; calculation of rocks in a frozen state; calculation during the transition period of freezing-thawing of rocks. With the appropriate calculation of Fourier numbers for each period and the aggregate state of moisture in dispersed rocks. The style of the article is scientific, the presentation is logical and evidence-based. The article is provided with a sufficient number of drawings, tables, graphs, which to a good extent illustrate the author's view on the calculation of soils of various physical composition. The material of the article is structured, and the content of the article corresponds to the set goal and objectives of the conducted research. The author also defines a further promising direction of research, which is advisable to direct to the study of the influence of the thermophysical properties of dispersed rocks on the range of changes in the main criteria of heat transfer, on the study of stationary heat transfer between a heated or cooled solid and the environment, in particular, the interval of change in the Bio and Stefan numbers, taking into account their variability for thawed and frozen rocks. The bibliography of the article is quite extensive, presented by both domestic and foreign sources, as well as links to Internet sources, contains both classic and new publications aimed at illustrating the material cited by the author of the article. The conclusions are reasoned and supported by evidence, the interest of the readership is determined by the author. In particular, the article, according to the author, will be useful both for engineers involved in the design of technical facilities in the cryolithozone, and for researchers in the field of structural physics and geocryology. From a methodological point of view, the article will certainly be of interest to teachers and graduate students studying in various specialties of the direction 1.6. "Earth Sciences" (specialty 1.6.7. "Engineering geology, permafrost and soil science"). and 2.1 "Technical Sciences", in particular, the educational specialty 08.02.05 "Construction and operation of highways and airfields".

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Eng

Eng